Description

“Speak Chinese please!” —Fatima Al QADIRI, “Dragon Tattoo”, Asiatisch, 2014

Shanzhai is a Chinese neologism for fake. The original meaning of the word in Chinese is mountain fortress, a stronghold which serves as a retreat for bandits and thus as protection from the access of authorities. While shanzhai versions of high-price labels from the electronics and fashion industry are a cheap alternative to prestige objects, this phenomena is becoming increasingly complex in the field of information technology, because “information wants to be free!”. (Stuart BRAND, Whole Earth Review, 1985)

This also applies to the cultural industry. Nate HARRISON has already shown this in his work Can I Get An Amen? (2004), a case study of an audio sample of a 6-second drum break (“Amen Brother”, the single B-side of the 1960s soul band THE WINSTONS). This very sample was responsible for the development of whole musical genres like drum and bass. These few seconds triggered an innovation thrust for electronic dance music. Nowadays, through intransparent licensing procedures, this most frequently sampled sound bit in digital music culture can now only be used legally by paying royality fees to a big company, which gained copyrights by an act of appropriation itself. The explosive spread of electronic musical genres and subgenres as it happens in the early 1990s would be impossible due to current legal practices.

The Chinese approach is much more relaxed in this respect. Shanzhai often has subversive qualities, it is a critical antipode to the excesses of the monopolization of copyright and licensing. This brings shanzhai closer to the ideals of the open design/maker movements (analogous to open source software). The controversy over counterfeits vs. originals in connection with shanzhai recalls the debate about appropriation art (Richard Prince, etc.). Sampling techniques used in hip hop music in the 80s and 90s causes a tightening of copyright regulations for intellectual property. On the other hand the completely fluid understanding of copy and original in China has led to a boom of modifications that cover all areas of life, from coffee shops and burgers to cars, literature, television programmes, entertainment and electronics to rock stars and medication.

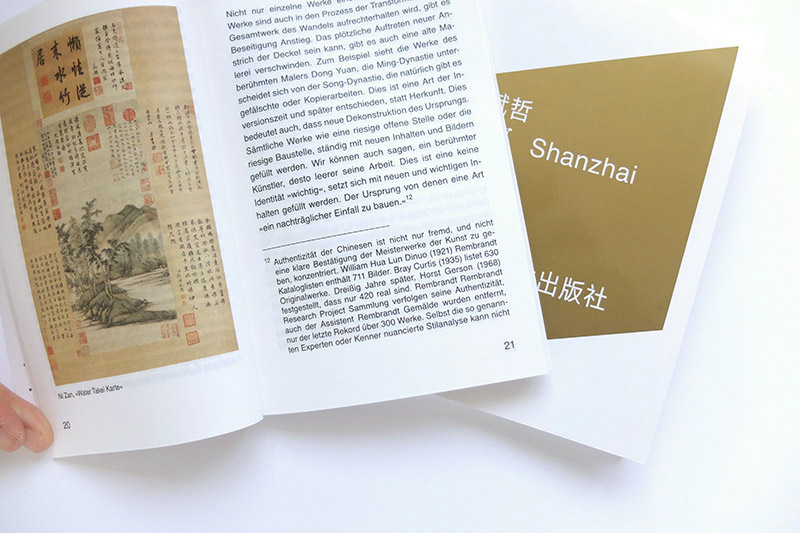

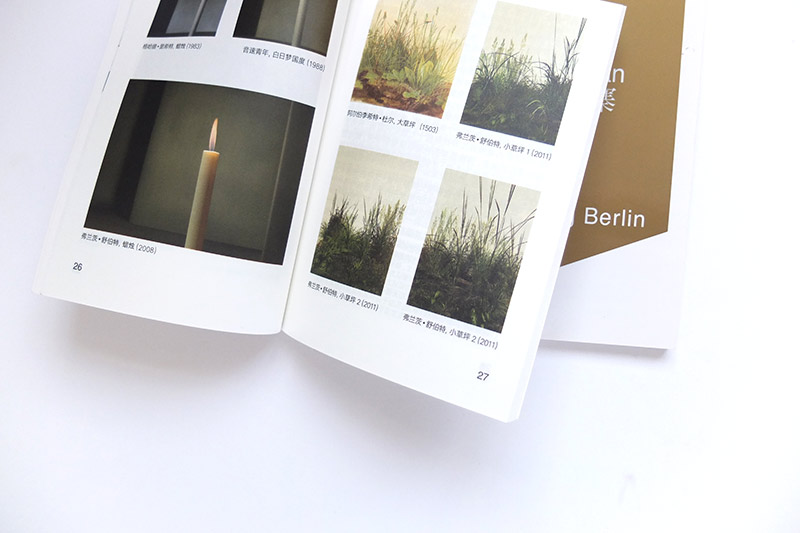

In his 2011 book Shanzhai 山寨 – Dekonstruktion auf Chinesisch (Merve, Berlin 2011), the philosopher Byung-Chul HAN has attempted to capture the many meanings of shanzhai, a phenomenon especially widespread in China. He distinguishes different concepts of “the original”, where copies can be simple fakes or bootlegs but also very advanced enhancements of an originary product. Copies of masterpieces are a traditional ways of practice and a tribute to the skills of the master.

The four volumes of Shanzhai apply the shanzhai principle to this philosophic text. The book, which is currently published in German only, was digitized, translated, edited, adapted, enhanced and then printed in four different translations as a shanzhai paperback mimicking the original format and layout.

The work not only focuses on cultural difference with regard to different conceptions of the original and the copy, but the original text becomes unreadable, apart from its poetic potentiality by way of contemporary translation software. Even the name of the artist could be a shanzhai alias.

– – – – – – – – – –

Colemanjoine –

I love to dress in this boutique. There are youthful and elegant things here. Once, on the recommendation of her husband, I even took 2 dresses at once

http://offeramazon.ru/bspb

Colemanjoine –

I love this store !!! Once I have discovered it for myself, I no longer waste time on shopping malls. There is no such assortment anywhere else! Moreover, it is being updated at a breakneck speed.

http://offeramazon.ru/p65u